Kenya’s agriculture is increasingly shaped by water scarcity, climate variability, and growing pressure on both farmers and natural resources. Irrigation is no longer just about increasing yields, but about resilience, efficiency, and long-term sustainability, especially in arid and semi-arid regions where water availability is unpredictable.

I am the founder of NuaSense, an IoT sensor company building field-ready sensors that measure soil moisture and other environmental parameters. Through our work with farmers, agribusinesses, and partners, I have seen how better data can fundamentally improve irrigation decisions on the ground. This article provides an overview of the main smart irrigation technologies used in Kenya today, their strengths, limitations, and how they fit together in practice.

Drip and micro irrigation systems for smallholder farms

For many smallholder farmers, drip and micro irrigation systems are the most practical step toward smarter water management. What makes these systems so valuable is that they control where water goes. Instead of wetting the whole field, they deliver small, frequent doses close to the plant’s root zone. In hot, windy conditions, that alone can reduce evaporation losses significantly. Micro irrigation also tends to reduce weed growth because the inter-row stays drier, and in some crops it can reduce disease pressure because leaves stay drier.

In Kenya, micro irrigation generally shows up in a few common forms. Drip lines and drip tape are widely used for vegetables and other high-value crops where targeted wetting is ideal. Micro‑sprinklers and mini‑sprinklers are more common in orchards and wider‑spaced crops, where a larger wetting pattern helps cover the root zone. Simple bucket, drum, or tank‑fed kits are often used for kitchen gardens and small nutrition plots, where affordability and simplicity matter most.

The important nuance is this: a drip kit is not automatically “smart.” It becomes smart when the design fits local conditions and when irrigation is scheduled based on crop needs, soil conditions, and weather, rather than habit. More about smart farming can be found in my latest blog article “Smart farming in Kenya”

Low-cost drip kits and gravity-fed systems

Low-cost drip kits are common across Kenya because they solve a real constraint: many farms operate on small plots, and electricity is either unreliable or too expensive. Gravity-fed systems, where water flows from a raised tank or drum, can work without any power and can be installed with limited tools.

But performance depends on details that are often underestimated. Gravity systems produce low pressure, so uneven fields or long pipe runs can easily lead to non‑uniform watering, where plants closer to the tank receive more water than those further away. Filtration is another critical factor. Many water sources in Kenya contain sediment and organic matter, and without proper filtering and routine flushing, emitters clog quickly. Finally, spacing matters. A layout that works well in sandy soils may perform poorly in heavier soils, so emitter spacing, flow rate, and crop layout all need to match local soil conditions.

When those basics are done right, the results can be immediate. I have seen farmers stabilize production through dry spells, grow higher-value crops more consistently, and extend the season to hit better market prices.

Water efficiency and yield improvements

The obvious benefit of drip and micro irrigation is saving water. The deeper benefit is control. Farmers can keep soil moisture in a healthier range by irrigating more frequently with smaller volumes. That reduces stress cycles and supports more uniform growth, which is especially important for vegetables.

In practice, these gains show up in several ways. Farmers often see more consistent yields and crop quality because plants experience less moisture stress. Fertilizer efficiency tends to improve as nutrients are applied in smaller, more frequent doses through fertigation. Labor requirements also drop significantly, especially on small plots, as farmers move away from manual watering with cans or hoses.

However, these benefits depend heavily on correct scheduling. Many farmers start with fixed routines because they feel safe, such as irrigating for the same duration every morning. The challenge is that water demand changes continuously with crop growth stage, temperature, wind, humidity, soil type, mulching practices, and canopy cover.

This is one of the reasons sensor-based irrigation is such an important complement. When farmers can see what is happening in the root zone, they avoid two common mistakes: under-irrigation that quietly reduces yield, and over-irrigation that wastes water, leaches nutrients, and can increase disease risk.

Adoption challenges and local manufacturing

Despite the potential, adoption is still limited by practical barriers. Upfront cost remains a major challenge, especially when farmers must also invest in seed, fertilizer, and crop protection at the same time. Maintenance and after‑sales support are equally important. Filters need cleaning, lines must be flushed, and leaks repaired, and without timely support, small problems can quickly discourage continued use. Water source reliability also plays a role, since drip systems cannot compensate for severe water shortages. Finally, quality variation in components can undermine performance, as poor‑quality emitters or fittings lead to uneven irrigation and frequent repairs.

Local manufacturing and assembly have helped reduce prices and make spare parts easier to find, which is a positive shift. But long-term success depends on training that goes beyond installation. Farmers need practical guidance on pressure management, filtration routines, flushing schedules, and day-to-day decision-making.

From my perspective, the best outcomes happen when micro irrigation is treated as a complete system: correct design, reliable filtration, farmer support, and increasingly, simple measurement tools like soil moisture monitoring to guide scheduling. That combination is what turns efficient hardware into a smart, dependable irrigation practice.

Sensor-based irrigation and soil moisture monitoring

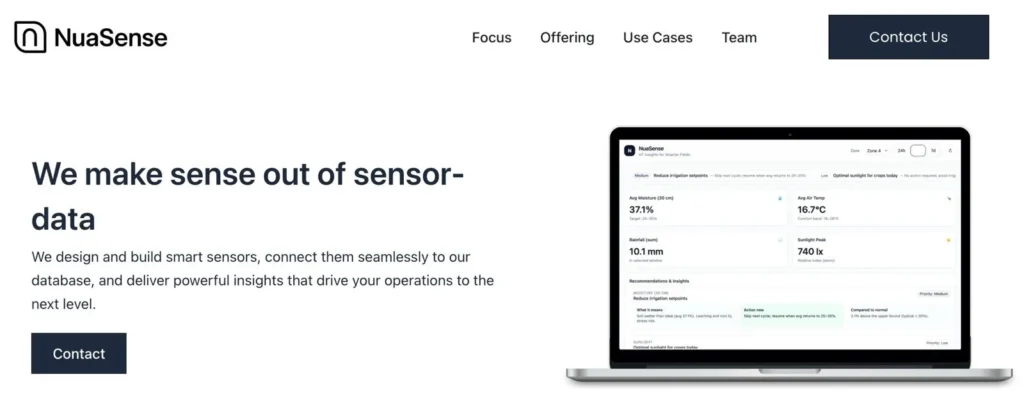

While hardware like drip lines determines how water is applied, sensors influence when and how much water should be applied. From my work as founder of Nuasense, I have seen that the biggest value of soil moisture sensing is not technical precision, but clarity. At Nuasense, we build field-ready IoT sensors designed specifically for real farming conditions in Kenya. Our focus is on robustness, low power consumption, and reliable soil moisture data that farmers and agronomists can easily translate into day-to-day irrigation decisions. It replaces guesswork with evidence from the root zone.

Soil moisture sensors and weather stations in Kenya

Most irrigation decisions are still made based on habit, visual crop stress, or fixed schedules. Soil moisture sensors help farmers see what is happening underground, before stress becomes visible. At a practical level, they help answer three simple questions: is there enough water in the root zone, how fast is the soil drying, and is irrigation water staying where roots can reach it.

In Kenya, affordable soil moisture sensors are most useful when they track trends rather than absolute numbers. Correct placement in the active root zone matters far more than sensor type. When combined with basic local weather data, farmers gain context on why soils dry faster during hot, windy periods and slower after rainfall or cooler days.

Automated scheduling and decision support

Sensor data only becomes useful when it is translated into clear guidance. In many cases, this does not mean full automation. Simple alerts or recommendations, delivered via dashboards or messages, are often enough to help farmers adjust irrigation timing and duration with confidence.

On larger farms and irrigation schemes, sensor data can also feed into controllers, valves, or pumps. This enables remote monitoring, faster detection of leaks or failures, and more consistent irrigation across blocks or fields.

Cost, maintenance, and farmer training needs

The main barriers to adoption remain cost, maintenance, and trust. Farmers weigh sensors against more visible investments like tanks or pumps, so the value needs to be clear. Systems also need to be robust, easy to install correctly, and supported locally.

Perhaps most importantly, sensors must be easy to interpret. At Nuasense, we deliberately design our systems so the technology stays in the background, while clear insights stay in the foreground. The goal is not to replace farmer experience, but to strengthen it with timely, trustworthy information from the field. When farmers understand why a recommendation is made, they are far more likely to follow it. Over time, this builds confidence and turns sensor data into a practical tool rather than an extra layer of complexity.

Solar-powered irrigation technologies in Kenya

Energy access is a major constraint in many farming regions of Kenya, which is why solar-powered irrigation has grown so quickly. Solar reduces operating costs and makes irrigation possible in places where grid power is unreliable and diesel is expensive or logistically difficult.

That said, solar irrigation is not just “a pump plus panels.” It is a system design problem: the water source, pumping height, pipe losses, daily water requirement, and storage all have to fit together.

Solar Pumps for groundwater and surface water

Solar pumps are used across Kenya to lift water from boreholes, rivers, shallow wells, pans, and storage reservoirs. Several design considerations determine whether a solar pump performs well in the field. Total dynamic head, which includes both vertical lift and friction losses in pipes, must be carefully calculated. The required flow rate needs to match crop water demand, not just pump capacity. For groundwater systems in particular, long‑term water availability must also be considered to avoid over‑extraction.

A common mismatch I see is under-sized or incorrectly specified systems. Farmers may buy a pump that works on paper but underperforms in the field because head and pipe losses were not properly accounted for. When systems are sized correctly, the benefit is clear: farmers gain independence from fuel costs and can irrigate more consistently. In Kenya, companies such as SunCulture have played an important role in scaling access to solar irrigation by combining solar pumps with financing, distribution, and farmer support, making the technology viable for small and medium-scale farmers.

Integration with drip and sprinkler systems

The biggest efficiency gains come when solar pumping is paired with efficient distribution such as drip or micro-sprinklers. But solar introduces a new scheduling dynamic: pumping output peaks at midday, which can encourage over-irrigation simply because “water is available now.”

This is where smart control becomes important. One common approach is the use of water storage tanks, which decouple pumping from irrigation timing and allow water to be applied early in the morning or evening, when crops use it more efficiently. Pressure regulation and proper filtration help protect drip systems as solar output fluctuates. Increasingly, sensor‑driven scheduling ensures that irrigation responds to actual soil moisture needs rather than simply following sunlight availability.

From a performance standpoint, combining solar pumping with soil moisture monitoring is one of the most powerful pairings in smart irrigation: solar solves the energy constraint, and sensors prevent the system from wasting water during peak pumping hours.

Economic viability and financing models

While operating costs can be very low, upfront investment remains the main barrier. The economics make sense when the system is reliably used for high-value production or when it enables an extra season of farming, but cash flow constraints are real.

Kenya has seen several financing approaches that help reduce this barrier. Pay‑as‑you‑go and asset financing spread costs over time, while leasing models allow farmers to access pumps and panels without full ownership. Cooperative ownership arrangements enable groups to share infrastructure, and bundled packages that combine equipment, installation, and service reduce complexity for end users.

One point I consider essential is after-sales support. Solar systems are long-life assets, but only if basic maintenance, warranties, and servicing are available. When financing is paired with strong support and good system design, solar irrigation can be transformational, turning irrigation from an occasional emergency response into a dependable production strategy.

Mobile, IoT, and data-driven irrigation management platforms in Kenya

Digital connectivity is rapidly reshaping agriculture in Kenya. Platforms such as Irri-Hub illustrate how IoT-based irrigation management systems can connect sensors, weather data, and irrigation infrastructure into a single interface for monitoring and decision-making. Mobile phones, expanding IoT networks, and cloud platforms are enabling a new generation of irrigation tools that connect field conditions with decision-making, often in near real time. These platforms do not replace physical irrigation infrastructure, but they increasingly act as the layer that ties systems together. More about IoT systems in agriculture can be found in my latest blog article “IoT applications in Kenyan agriculture”

Mobile advisory services and SMS-based alerts

Mobile advisory services are often the most accessible form of digital irrigation support. By delivering recommendations via SMS, USSD, WhatsApp, or smartphone apps, they reach farmers who may not have access to computers or advanced equipment.

In practice, their value depends on relevance and timing. Generic advice has limited impact, but localized recommendations based on crop type, growth stage, soil conditions, and recent weather can meaningfully influence irrigation decisions. Even simple messages, such as alerts to delay irrigation after rainfall or reminders during peak water-demand periods, can help farmers avoid unnecessary watering and reduce risk.

IoT controllers and remote system monitoring

IoT-enabled controllers and gateways allow irrigation systems to be monitored and, in some cases, controlled remotely. This is particularly useful for larger farms, greenhouses, and irrigation schemes where manual checks are time-consuming and inconsistent.

Remote monitoring helps users track pump status, pressure, flow, and sensor readings without being physically present. It also enables faster response when something goes wrong, such as a leak, a blocked line, or a pump failure. While full automation is not always required or appropriate, even basic visibility into system performance can improve reliability and reduce downtime.

Data platforms for farm-level and regional planning

At a broader level, digital platforms make it possible to aggregate irrigation and soil data across multiple fields or farms. For individual farmers and agribusinesses, this supports better comparison between plots, seasons, and practices. For cooperatives and service providers, it enables more targeted advisory and maintenance support.

At county or regional scale, aggregated data has the potential to inform water allocation, infrastructure planning, and drought response, provided it is handled responsibly and transparently. From my perspective, the long-term impact of smart irrigation in Kenya will come from connecting reliable field-level data with practical analytics that support both productivity and sustainable water management.

In conclusion, smart irrigation in Kenya is not about a single technology, but about integrating efficient hardware, reliable energy, and data-driven decision-making. As someone building IoT soil moisture sensors at Nuasense, I am convinced that accessible, farmer-centric data will be a key enabler of sustainable irrigation across the country.

Ready to make your irrigation smarter?

The opportunities described above are not abstract or distant. Improving water efficiency, strengthening resilience to climate variability, and making better day-to-day irrigation decisions are all practical steps that farms in Kenya can start taking today with the right tools and support.

At NuaSense, we actively work on these opportunities by providing real-time field data through robust soil moisture sensors, turning that data into clear irrigation insights, and supporting deployment models that work for Kenyan farming realities. Our focus is on helping farmers, agribusinesses, and irrigation managers move from fixed routines and guesswork toward smarter, data-driven water management.

If you are interested in making your farm more efficient, resilient, and future-ready, we would be glad to hear from you. Get in touch with us to explore how smart irrigation and field data can work for your specific farm or project.